Last Updated on 2023-09-17 by Joop Beris

A friend triggered me with a question the other day. He was wondering: are we happier today in our modern society than people in the past? That’s a very complex question with many facets to consider. Who are we comparing? How are we going to make that comparison? To what period in history are we comparing our modern time? And what is happiness, exactly? Despite the many obstacles, I decided to do a small exploration of this vast topic. Prepare to set your time machine for 1022 CE to explore the question: are we happier?

What is happiness?

The most basic question underlying this little exploration is the question of what we mean when we use the word happiness. So that is where we need to start our exploration. It may come as a surprise to you that this is not a very easy question to answer. We all hopefully know the feeling of happiness but it’s not so clear where this feeling comes from. It’s also not clear if the source (or sources) of happiness are the same for people or if they’re different. Some people seem to find happiness in relationships with others, others in money or status. Our environment matters for our happiness and biology plays a role too.

Philosophic thought

With so many contributing factors, it’s hard to find out what constitutes “the happy life”. It’s also clear from examining history that different times and different cultures differ greatly about their opinion of happiness. Over the centuries, philosophers pondered the question of where happiness comes from and what constitutes the happy life. Let’s look at some of their conclusions.

Ancient Greece

Democritus is the first person in the western world who pondered the question of happiness. He suggested that happiness is not a result of a favourable fate or good luck but rather a case of mind. Happiness therefore is a subjective state, it’s not objective. Plato in The Republic writes that only those who are moral can be perfectly happy. A moral person understands the four Cardinal Virtues (prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance). Happiness also comes from fulfilling the social function one has. Socrates introduced the “science of happiness” and claimed that complete virtue (good moral character) was the prerequisite for happiness. Similar attitudes show up with other ancient Greek philosophers such as the Stoics, who emphasize virtue as the road to happiness, not relationships, money or status.

(photo by Matt Neale from UK)

Christianity

St. Augustine of Hippo, an early Christian philosopher, suggests that unhappiness is caused by placing your love in people or things. Orienting yourself towards God allows you to become happy. God is the source of all love and from him all love flows. By orienting yourself towards God, all your other loves will fall into place.

Thomas Aquinas, a much later Christian philosopher writing in the 13th century, combines Aristotelian virtues and Catholic theology. Intellectual and moral virtue help us to understand the true nature of happiness, which is ultimately a supernatural unity with God.

Islam

Al-Ghazali was a Muslim theologian, philosopher and jurist who lived in the 11th century CE. He postulates that complete devotion to God is the only way to achieve ultimate happiness. He advocates observing the ritual requirements of Islam and avoiding sin.

Early modern philosophy

In more recent times Jeremy Bentham, the father of modern utilitarianism, defined happiness as an experience of pleasure and a lack of pain. Arthur Schopenhauer on the other hand, sees the fulfilment of a desire as happiness, though this feeling is only temporary because as soon as a desire is fulfilled, a new one pops up to take its place. Friedrich Nietzsche (see, I told you I could work his philosophy into my posts) had another opinion again, postulating that an increase of power or the overcoming of resistance leads to happiness.

Modern philosophy

Victor Frankl, neurologist and psychiatrist, emphasizes meaning, the value of suffering and a responsibility to something greater than oneself as prerequisites for feeling happy. Finally, Sonja Lyubomirsky, professor of psychology, bases her explanation of happiness on research done on twins. She concludes that happiness is 50% genetically determined, 10% is based on personal circumstance and 40% subject to personal control and influence.

No clear definition

It seems that after more than 2500 years of attention to the subject by some of the best minds, we still don’t have a proper understanding of what makes people happy. Perhaps this is due to the fact that happiness has different causes for different people or perhaps there is a deeper cause for happiness underlying all causes mentioned.

Something else that complicates matters, is that people confuse comfort with happiness. People in western Europe today undoubtedly have a higher standard of living than they did 1000 years ago. That is not the question though. Are we happier because of this higher standard of living?

Lacking a cause of happiness makes our exploration more challenging. If we’re not sure what causes happiness, we can’t come up with a complete answer to the question if we are happier than people in the past.

(Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.com)

Why 1022 CE?

Picking a place to compare to wasn’t very hard. I could have chosen any area of the world but that would increase the complexity of the comparison even more. Also, it wouldn’t make sense to compare modern Europe to feudal Japan, for instance. For that reason I want to focus this little exploration on Western Europe. For the time, obviously 1022 CE is exactly 1000 years ago. I picked this time because 1000 years is a nice, round number but also because it allows me to address an issue with our perception of the European Middle Ages.

Asking the question “are we happier in our modern society” and then comparing with the Middle Ages seems like an open and shut case. Most people would immediately say “yes” because of how we tend to view this period in history. When we say Middle Ages, people generally think of a time of decline, a time of war and violence, ignorance, superstition, rampant disease, filth, brutality and torture. These were our Dark Ages.

The problem of the Middle Ages

Granted, all those things did occur during this period in our history. But we have to consider that we are talking about a period that started in the 5th century CE and that lasted until about 1500 CE. That’s a period of roughly 1000 years. More time passed between the start of the Middle Ages and their end than between the end of the Middle Ages and our own time. This wasn’t a consistently hellish time. Just like now, people had bad times and good times. Popular culture focuses on the bad times not because they were predominant but because they appeal to a modern audience.

An image problem

(Rood screen in St. Mary’s church, Old Hunstanton by pam fray is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0)

Unfortunately, the Middle Ages suffer from an image problem. That image was popular with 18th century Enlightenment thinkers, who saw their own time of reason and knowledge in stark contrast with the ignorance of the Middle Ages. That negative image is still actively perpetuated by film and TV today. When you next see a show set in the Middle Ages, pay attention to the way they show people of that time. Almost invariably, the extras is in the background (not the main actors) are portrayed as dirty, ugly, unkempt and dumb.

But if that image is wrong, what was 1022 CE really like? What did the lives of ordinary people look like? Were they happy? How can we even tell?

Source material

A problem with most periods of history, is piecing together the story of what happened. The availability of source material varies greatly and usually the further back in time we go, the less information we have. Historians work with a wide range of sources that fall in two major categories: textual sources and non-textual sources.

Textual sources

Our history begins with the time humans started producing written texts, everything before that time is called prehistory. For the medieval period, we have a variety of textual sources:

- Descriptive sources

These are sources where the author provides the reader with a record of events, people, areas or circumstances. This can be a list of kings, a report of a battle, a record of a famine that struck a certain region, for instance. - Legal sources

Sources that deal with laws or jurisprudence. These can be a set of laws in a city, a record of legal proceedings or rules that govern a certain monastic order or texts like that. - Administrative sources

These are sources that deal with the administration of people, goods, finances and lands. Everything from designating someone owner of an estate, an inventory of a storehouse, a census of a village or taxes collected. - Scientific, didactic or technical sources

Think texts used in schools or universities, or a document on the fine art of playing chess , hunting, swordsmanship and encyclopedias. - Faith and philosophy texts

During the Middle Ages, the Christian faith was dominant in much of Europe and as such determined much of daily life. As such, many religious texts were produced, ranging from theological treatises to the practice and experience of faith in daily life. - Literature

Apart from practical texts, people in the Middle Ages also produced novels, poetry, plays and songs. - Epigraphs

These are texts that have been left on material such as stone, wood, metal and bone. We find these on buildings, as part of a grave stone or a commemorative plaque but also as a mark a craftsman left on his products. - Linguistic sources

Finally, the Middle Ages left their mark in language. Place names, names of people but also words in common use, have an origin that traces back hundreds of years. The etymology can tell us something about the past.

Non-textual sources

Apart from documents, we have a whole host of non-textual sources that can tell us something about the past. For the Middle Ages, we have the following types:

- Utensils

People in the Middle Ages crafted a wide variety of utensils, ranging from tools and weapons to furniture and clothing. These utensils provide us with a lot of information such as taste and wealth but also professions. - Figurative sources

Medieval people produced visual art in the form of sculptures, drawings, paintings but also carvings in furniture or even comical graffiti. - Architectural sources

Many buildings in Europe date back to the Middle Ages. The first example that comes to mind is probably the cathedral. But the same is true for castles, city halls, custom houses, guild halls, warehouses, monuments, etc. Often these buildings were decorated with sculptures and paintings, leaving us even more information. - Traces in the ground and landscape

Over the centuries, people have left lots of traces of their activities in the ground. Burial mounds and grave yards, foundations of castles or other buildings but also buried trash heaps, ancient road or allotment patterns, these are all still visible in the ground.

(Photo by Pille Kirsi on Pexels.com)

Problems with the sources

Reading through this list, it seems as if we have an abundance of sources and for some times and some places, this is true. For other times and other places, we have virtually nothing and historians are reduced to making educated guesses. The historical record is often fragmentary and there are lots of things we don’t know. For instance, before the 12th century CE, people in Western Europe didn’t put many things in writing. Textual sources from this time period are rarer than from the Roman period or the late Middle Ages.

Another problem we have is considering who put things in writing and for what reason. Certainly for the early Middle Ages, common people generally couldn’t read or write. While we have texts about them, we have little sources from them. That means we have to consider the motive of the author along with what he or she writes. A play might depict farmers as stupid, boorish and loud but perhaps the author intended to illustrate how much more noble and sophisticated the nobility was.

Life in 1022 CE

With all those caveats addressed, let’s take a look at what life was like in Europe 1000 years ago, in 1022 CE. Hopefully this will help answer the question: “Are we happier?”

The first thing to notice is that Europe in those days was very different from the Europe of today. After the slow collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, there was no central power in Western Europe. There were no nation states either. Western Europe fragmented into small territories ruled over by local warlords who fought each other over land. Many cities emptied and trade came almost to a halt. There was even reforestation and a retreat of agriculture as populations declined.

The following paragraphs paint the situation with a very broad brush because it’s impossible to do justice to the many regions, peoples and events in the short space of this article.

Europe in 1022 CE

By the year 1022 CE, Europe had changed a lot from the state it was in after the Roman collapse. A quick look will help us to paint the picture of what the continent looked like and to answer the question: are we happier?

Western Europe and the north

By the year 1000, the situation had changed dramatically. Although not yet nation states, the domains of the local warlords had expanded and more or less solidified into kingdoms and empires. The kingdom of France was internally divided, though. Powerful lords battled each other for land while the title of king had become largely irrelevant. Inspired by charismatic rulers such as Charlemagne, the many territories that made up the Holy Roman Empire had an emperor crowned by the pope in Rome. The kingdom of Burgundy, though technically part of the Holy Roman Empire, was largely independent.

The kingdom of England was still very new, unified for the first time in 927 CE under king Æthelstan. Much of what would later become the United Kingdom was ruled by the Danes. Speaking of the Danes, Viking raids still sailed from Norway, Sweden and Denmark in the 11th century though the spread of Christianity in these lands meant this slowly came to an end.

Eastern Europe

In Europe further to the east we find the Slavic kingdoms of Poland and Hungary, along with several other Slavic realms. The Poles were Christians and allies of the Holy Roman Emperor against pagan invaders from further east. The kingdom of Hungary was home of the Magyars. As recent as 950 CE, the Magyars burned, pillaged and enslaved people as far west as the Rhineland. It took a joined effort of the Germanic knights to stop these raids, giving their leader Otto the status necessary to claim the title of Holy Roman Emperor, becoming Otto the First. His second successor, Otto III, attempted to turn the Magyars into allies by converting their rulers to Christianity and bribing them with treasure. He succeeded brilliantly and Stephen the First of Hungary would go on to become a staunch ally of Rome. He is still revered today as Stephen the Great.

(Unknown author, source Wikimedia)

Southern Europe

Further south, we find the Byzantine Empire, the remnant of the Roman Empire. After centuries of decline and shrinking borders, the empire was experiencing a golden age under the Macedonian dynasty. It managed to strengthen and even grow its borders, doubling its size in the space of just 50 years. In Italy though, Venice managed to sever its feudal ties with the Byzantines and became independent, forging its own Mediterranean republic. Other Italian cities such as Pisa, Genoa and Amalfi followed suit.

Across the Mediterranean, they came in touch with the Fatimid Caliphate, an Islamic state that took over much of North Africa in the 7th century CE. The Fatimids were open to trade with the Christian states to the north, something from which cities like Venice profited. That was until Al Hakim, the “mad caliph”, came to power and destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. This sent shock-waves through Christian Europe and was one of the catalysts of the Crusades.

On the western side of the Mediterranean, we find that the Iberian peninsula is home to another Islamic state: the Caliphate of Cordoba. Although destined to fall apart soon, in 1022 CE it was still a beacon of learning and culture. Just to the north of the caliphate, a number of smaller Christian kingdoms hang on, Castile, Aragon, Leon and Navarre. These kingdoms began pushing south as the caliphate splintered, beginning the centuries long process of the Reconquista.

Society in 1022 CE

Society followed a feudal structure, forming a complex web of mutual contracts and obligations. In this system, the king was at the top of the feudal pyramid but was dependent on his most powerful vassals to rule the lands the king granted them. Most noble families found ways to make their status hereditary and in practice, the king was often not the most powerful person in the land!

From the king and his most important vassals down, nearly everyone was part of this feudal structure. The king’s vassals had vassals of their own who often had vassals below them as well and so on. At the very bottom of the pyramid we find the farmers, most of whom were not free but had sworn fealty to a local lord. In return for the protection of the lord, the farmers worked the fields, paid taxes in the form of goods produced or might even be drafted into military service should their lord go to war.

The Christian church was also a major landholder in these days so the feudal overlord in a region could be a bishop or the abbot of a monastery. Farmers worked the often vast estates of the monasteries or abbeys, just as they did for secular landholders.

In general, we can say a number of things about Western European society in 1022 CE:

- 80% of the population worked in the agrarian sector, of these, 70% were serfs.

- There is little specialization. Farms generally provide their own needs in food and often in tools and clothes as well. There is little surplus.

- Natural conditions determine what people produce.

- The nuclear family is the basic unit of society.

- Multiple families together form communities, typically living in a village.

- There are large legal differences in agrarian society, ranging from farmers who are little more than slaves all the way up to free people like nobles and clergy.

- Sociopolitical order is determined by a mixture of (military) power and ownership of land.

- Technical and business innovations happen slowly and with large regional differences.

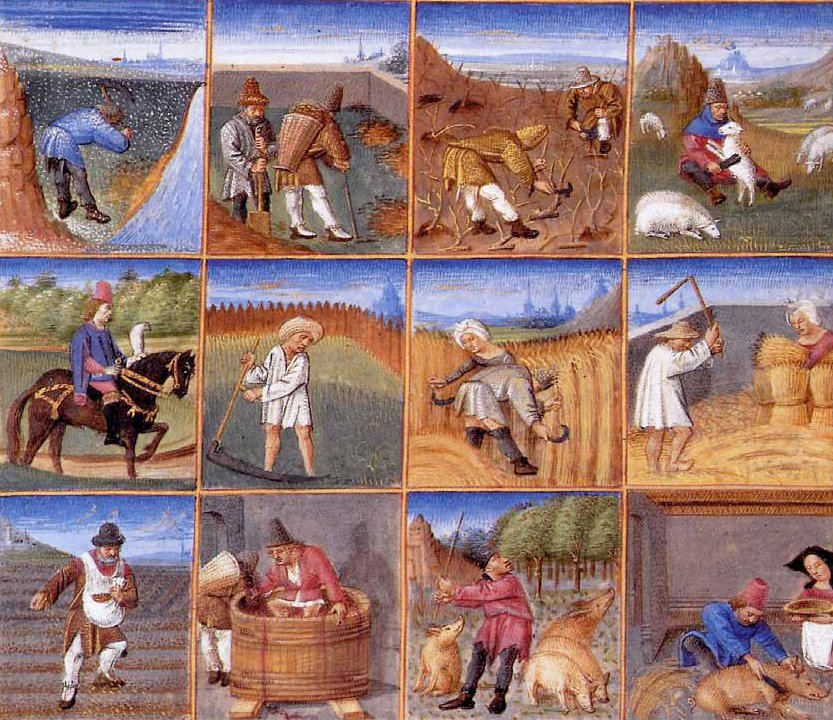

Life of farmers

Since the vast majority of people were farmers, let’s examine their lives a bit more closely. We’ve just seen that farmers usually aren’t free people. The pace of their lives was governed by the rising and setting of the sun and the changing of the seasons. Without the benefit of machines, their work was hard. When crops failed, there was neither the infrastructure nor the resources to bring in food from elsewhere, which meant that people had to go hungry. If someone got injured or ill, there was little in the way of healthcare to fall back on. People probably knew some herbal remedies but mostly it was up to the immune system of the affected person if they lived or not. Infant mortality was high and life expectancy was around 40 ~ 50 years.

Obligations

Medieval farmers had obligations to their lord. As mentioned above, farmers were often required to accompany their lord if he went to war. This meant actually participating in battles, fighting the enemy. Obviously this was a dangerous activity, especially if untrained, poorly equipped farmers faced trained soldiers or mercenaries. Since only free men were required to fight for their lord, lots of free men surrendered part of their free status to escape this duty.

Other duties included working the fields of the local lord for a number of days per week, maintain local infrastructure such as roads or bridges and surrendering part of the harvest to the lord in payment for the land the farmer leased from his lord.

However, a feudal contract was a mutually beneficial agreement. The lord had his share of the benefits but so did the farmer and his family. For one, the lord was required to protect the farmer from dangers such as raiders and pillagers. Additionally, farmers leasing land from the lord couldn’t be removed from that land when it pleased the lord and the lease became hereditary, meaning the farmer’s children would inherit the lease. In theory then, the family had a place to live and a source of income for many generations.

A hard life but an unhappy one?

Compared with the life of the average person living in Western Europe today, life for the medieval farmer was undoubtedly a lot harder. But that doesn’t necessarily mean an unhappy life. When we look back, it’s very easy to judge the Middle Ages from our perspective. We modern people may find the life of medieval farmers dull, hard and unfavourable to happiness. But doesn’t that say more about us than it does about the actual happiness or unhappiness of medieval farmers? Are we happier or could it be them?

Comparing 2022 CE and 1022 CE

The year 1022 CE actually has a lot of things going for it when compared with 2022 CE. For starters, those medieval farmers had an average of 8 weeks in a year off due to the many religious holidays. In the Netherlands, the average now stands at 4 weeks in a year. Celebrations in the Middle Ages often weren’t small affairs either. Even poor villages could have wedding celebrations take a week, with everyone joining in, even the very poor.

Less worries

In addition to more free time, medieval farmers had less to worry about than we do, or at least their worries were more personal than ours. If bad things happened, they were painful and close but because of that, they were also understandable and small in scale. Often, they could personally influence the outcome. In fact, their whole world was smaller.

Things are different for us. In addition to the things we have to worry about personally, we are also constantly bombarded with news from every corner of the world. Most of that news is bad and scary. It’s not personal and as individuals we are powerless to change any of it. We worry about distant wars, natural disasters and the impact of climate change on our environment. Such news would simply not reach medieval farmers or if it did, it was much later and too far away for them to be concerned about it.

Less wants

We’re not just bombarded with bad news, we are bombarded even more frequently with advertising. Many companies try to sell us products or a lifestyle that people often can’t afford and of course don’t really need either. Advertising influences how people feel about themselves, usually not in a good way. It can be used to sell harmful products, promote unhealthy lifestyles and give people unrealistic expectations of what their life should be like.

Such problems didn’t affect medieval farmers, of course. There was no advertising and most of their immediate neighbours led a very similar life in terms of wealth and belongings. Of course there was inequality and some people were very rich compared to others but a medieval farmer was rarely confronted with this fact directly.

In addition to that, in Medieval times people had an idea of a social order divided into three: those who pray, those who fight and those who labour. These three estates were the clergy, the nobility and the peasants. They believed that this was the ideal social order, endorsed by the Bible. Those who dutifully fulfilled their role in society, would be rewarded in the afterlife.

Nihilism

In modern western Europe, societies became increasingly nihilistic after entire generations lost their Christian faith. Most people don’t believe in anything any more and while this had a liberating effect, it also meant that people lost their grounding, their purpose. We have structured our society so that we never have to ponder existentialist questions when we don’t want to because we are constantly offered distraction. We have replaced the certainties of faith by the short-term dopamine hits of social media or binge-watching streaming media. Or people find their meaning in work, sports, friends or going out.

This was much less of a problem for our medieval farmers. The meaning of their lives was not found on this Earth but in the Christian concept of the afterlife. By living their lives according to the teachings of the church, they could secure their place in heaven. This made their life both purposeful and bearable. Whatever suffering they experienced in this world, lost its hopelessness in comparison with an eternity of bliss after death. This belief was of course an illusion but some might argue that for the majority of people, it was a necessary illusion.

Serfdom

Some of you may be thinking that this is all well and good but we shouldn’t forget that around 70% of medieval farmers were serfs, little more than possessions of the lords. That is undeniably true. While being a serf in the Middle Ages wasn’t as bad as slavery was in Antiquity, it still meant you weren’t free. The lord didn’t own the serf, the lord owned the labour of the serf. Serfs were tied to the estate of the lord, couldn’t move away and often couldn’t even marry without permission from the lord. Fortunately for us, serfdom is something we’ve gotten rid of in modern times.

Or have we? Many people in Western Europe today are in debt. Whether it is a mortgage for their house, a student loan that needs to be repaid or another form of debt. How many people own the house they live in? We may own our labour but modern society more or less compels us to sell our labour for money to repay our student loan or mortgage. While a medieval lord had some obligation to care for serfs, how much does the bank care for us? So can we really say that we are that much better of in this respect?

(Photo by imustbedead on Pexels.com)

Resilience

A final point I want to raise, is that of resilience. Modern European society offers us a great deal of comfort. If we’re cold, we turn up the heat. Lights comes on at the flick of a switch and water just runs out of the tap. When we’re in pain, we take an easy to obtain pain killer. When we don’t feel so well, we call in sick and stay home or go see a doctor. Food and things are delivered on our doorstep when we need them and our favourite series starts when we want it. If we have to wait for something, we complain and when one of these things don’t work for whatever reason, it’s difficult to deal with for us.

A medieval farmer lacked all of these comforts. Sure, they could throw an extra log on the fire but they had to chop the wood themselves. Obviously there was no electricity and water had to be carried from a well or stream to the home. Pain medication or doctors were unavailable too. People who were in pain or ill would either get better or not. No matter if you felt bad, there was always work to do. Food or anything they needed, they made themselves. Everything took time because things were done by hand.

While the situation of the Middle Ages may seem impossible for modern people to deal with, I think people back then were used to it and as a result, much more emotionally resilient. Instant gratification didn’t exist so people didn’t expect it. A tooth ache still hurt of course but in a world without pain killers, people were much more used to pain. It was part of their lives. The same is true of death, of cold or of loss. Of course such things affected people in the Middle Ages but they had to be physically and mentally tough to deal with it.

Conclusion

So are we happier today than people in Western Europe back in 1022 CE? If you’ve read all of the above, I think you may agree with me that it’s not an easy question to answer. Even though this is a long blog article, there are so many factors to consider that it can scarcely do the topic justice. Your answer depends on how you look at it.

One of the conclusions we can draw, is that we should not consider ourselves the obvious winners. When it comes to happiness, a lot has changed in the last 1000 years. The idea that human beings have a right to happiness is quite a recent invention. It wasn’t until the Enlightenment that it entered our collective consciousness. Of course people desired happiness before then but I think they better understood that happiness comes in small doses.

I think it’s possible that our desire for happiness is actually contributing to a feeling of discontentment. The idea that we should be happy as a general principle may be very unrealistic and only achievable by taking mood-altering substances. However, some may argue that tampering with brain chemistry is not real happiness.

Are we happier? Personally I am not so sure we are but you’ll need to make up your own mind. Tell me what you think in the comments!

Sources

This article is not just my opinion but I’ve drawn upon a lot of material to write it. Some of the most important sources include the works of the following people/sources:

- Prof. D.E.H. de Boer (historian)

- Prof.dr. J. van Herwaarden (historian)

- Prof. J. Scheurkogel (historian)

- Prof. Dr. Peter N. Stearns (historian)

- Dr. Eleanor Janega (historian)

- World History Encyclopedia

- Encyclopedia Britannica

- Magellan TV History Time

- Wikipedia

- History Collection

- Medievalists.net

- Positive Psychology

Hi Joop!

Very interesting topic and well researched, as always.

I will make this short and not go into details. I believe happiness is a transitory illusion based on expectations and the element of time (change), and because of that, I don’t believe it is possible to truly quantify what we call happiness between then and now, here or there, or in any way whatsoever.

Thanks for all of your posts. Always thought-provoking.

Jim

Hi JIm,

Thanks for the kind words and reading my posts, as always! Glad you found this one interesting because it took a bit of doing.

I think I agree with your statement about happiness. Happiness, like other emotional states, is highly subjective and probably influenced a great deal by our subconscious, our drives, etc. We recognize happiness when we experience it but pinpointing where it comes from is a lot harder, maybe even impossible.

Thanks for being a returning visitor and reader!