Last Updated on 2022-07-08 by Joop Beris

Forgery, a book review is my review of “Forgery, the split pen of bible-writers” the title of a small book I picked up a long time ago and that I’ve recently been rereading. As far as I know, Amazon does carry it but only in a Dutch edition and I’m not sure it’s ever been translated. The author is Jacob Slavenburg, a Dutch historian who has written several publications about early Christianity and gnosis. He’s also a co-translator of the Nag Hammadi library into Dutch.

Despite the somewhat heavy subject of the book, it is very accessible, even to people who’ve never looked into the history of the Christian gospels. Slavenburg manages to capture the reader and doesn’t become boring or overly repetitive despite the fact that he goes over several sources while comparing different verses. The repetition is done for effect and it works. It is hard to put down this book and not think that holy books are rather akin to sausages in the sense that you shouldn’t see either being made.

Slavenburg divides his book into three major parts. Part 1 looks at the canonical gospels that have been incorporated into the New Testament. Part 2 takes a closer look at the so-called apocryphal texts that the early church deemed unfit to be part of the canon. Part 3 looks at what the consequences are of this process of division. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that for part 2, the author leans heavily on the Nag Hammadi library, since he was involved in the translation of these documents into Dutch.

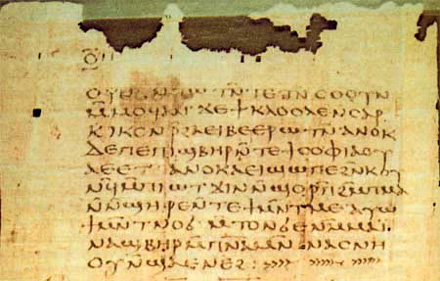

For those unfamiliar, the Nag Hammadi library is a collection of Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945 by a local farmer named Muhammed al-Samman. The most well-known of the manuscripts found in the library is the Gospel of Thomas, which most scholars agree pre-dates most of the canonical gospels. Needless to say that for biblical scholars, the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library is every bit as exciting as that of the Dead Sea scrolls.

Part 1, the gospels that made it into the Bible

In this part, Slavenburg takes a closer look at the canonical gospels and other writings that became a part of the Christian New Testament. He examines the question of whether or not these writings are historically reliable and draws some conclusions which may be shocking to Christians, such as the fact that we have no idea who wrote the gospels of Marc, Luke, Matthew and John. Slavenburg looks at how these writings came about, drawing on older, much simpler texts and how the current, accepted versions have undergone thousands of alterations, both intentional and non-intentional. Often these alterations were done to make the story support the theology of the time. Facts from the Bible that are taken for true by millions of Christians worldwide, are simple fabrication or mistranslation, for instance the virgin birth of Jesus or his place of birth.

After reading this part, you will come away amazed at how arbitrary and unreliable the canonical gospels actually are.

Part 2, the gospels that didn’t make it into the Bible

These are the so-called apocryphal gospels, from the Greek apókruphos, which means hidden. The manuscripts found at Nag Hammadi mostly belong to the collection of Biblical apocrypha and the explanation offered for why there were buried in the desert is that the owners of these documents, most likely a nearby monastery, feared excommunication if they were found in the library of the monastery.

Interestingly, according to Slavenburg, these documents paint a different picture of Jesus compared to the New Testament today. There is much less emphasis on Jesus’ alleged divinity. In fact, Jesus isn’t even born a deity (and not from a virgin either). Instead he received the divine spark of the Christ essence upon his baptism by John the Baptist in the river Jordan. Missing also is the obsession with sin and especially Original Sin. The emphasis on Jesus’ crucifixion is therefore also mostly absent. Perhaps most important though, is that Jesus’ message is different. It’s not faith in Christ that saves you, it’s not necessary to obey the law of the church on Earth to be rewarded in heaven after you are dead. Instead, the state of heaven can be experienced right here, right now. Knowing yourself leads to understanding of God. This way, anyone can have a personal relationship with God. There is no need for priests, no need for temples and no need for a Holy Church.

Jesus almost comes across as an oriental mystic, a Buddha-like figure who has experienced an epiphany, attained a state of heightened understanding of the world and is teaching this to his followers, showing them the way rather than being the way to salvation.

In the early church there was room for different interpretations of what Christ’s teaching was, there was room for personal freedom in belief. Slavenburg writes that this began to change when the persecution of Christians in the Roman empire stopped and Christianity itself became the official state religion. Suddenly there was a need for an established canon, a proper doctrine. The problem was that many texts existed, in different languages and in different regions. In the process of compiling these texts into canon, choices had to be made. Texts were selected that seemed to support a central authority in the church, errors in doctrine were “corrected” according to the theology of the time and of course new errors were introduced by mistranslation and errors while copying. The New Testament as we know it today, was shaped in the 3rd and 4th century CE. and with important consequences.

Part 3, the forgery and its consequences

In the process of standardising the beliefs of the early Christian church, a lot of things were changed. There was less emphasis on Jesus the man, gone was the personal relationship with God, gone also was the equality of man and woman that the apocrypha show. In their place came Jesus as the Christ, salvation through belief in the death and resurrection, damnation for those not of the faith (or of the wrong interpretation), oppression of the female and emphasis on the afterlife, be it heaven or hell. The church now had a strict hierarchy, with the bishop of Rome as the most important figure because he was the successor of Peter, the rock on which Jesus built his church.

The direct relationship with God had been amputated, just as the kingdom that Jesus promised his followers. They were transported to the afterlife or to the end of times even though the apocrypha seem to make it clear that Jesus meant that both could be attained in the present.

Conclusion

Slavenburg makes a convincing case for the New Testament as we know it, to be a (deliberate) forgery or at the very least the result of a fairly arbitrary and unreliable process of alteration, fabrication, (mis)translation and selection. A process that wasn’t so much about preserving the teachings of Jesus (if there ever was such a person) but rather to help lay a foundation for the emerging Christian church as it rose to power, often changing the text to match the desired result. It is a forgery so successful that it has managed to fool much of the world for over 1500 years.

Even a man as bright as C. S. Lewis, who argued in his apologetic book “Mere Christianity“,

Either this man (Jesus) was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronising nonsense about his being a great human teacher.

fails to realise that there is a fourth, much more logical option. Much like Lewis’ own Aslan, the figure of Jesus that we read about in the New Testament is a fictional character, a literary creation by men with an agenda. Lewis like so many, makes the mistake of perhaps not taking the Bible literally but at least to take it as the accurate word of God where it comes to the words, deeds and ultimate fate of Jesus. Slavenburg shows this fallacy all too clearly.